You’re at work when you hear a text notification on your phone. You check it, maybe send a quick reply, then have to take a few minutes to get back to the task at hand. Or perhaps you’re at home and decide to verify a fact mentioned on a show you’re watching. You determine the truth (or fiction) of the matter, then realize you missed an important plot point and have to rewatch the last few minutes of the show.

Second-screening is an increasingly common aspect of people’s lives. Depending on who you talk to, it’s either a natural response to multiple devices or an attention-sapping issue that impacts productivity and memory.

At present, there isn't enough data to definitively determine how second-screening impacts cognitive processing. We can, however, explore when, why, and where Americans use two devices at once. To do so, Hughesnet® surveyed 2,129 Americans about their second-screening habits and experiences. We found that the habit is widespread, that many people express concern about how long they second-screen, and that many worry about the habit's impact on their attention spans.

How Often Do We Second-screen?

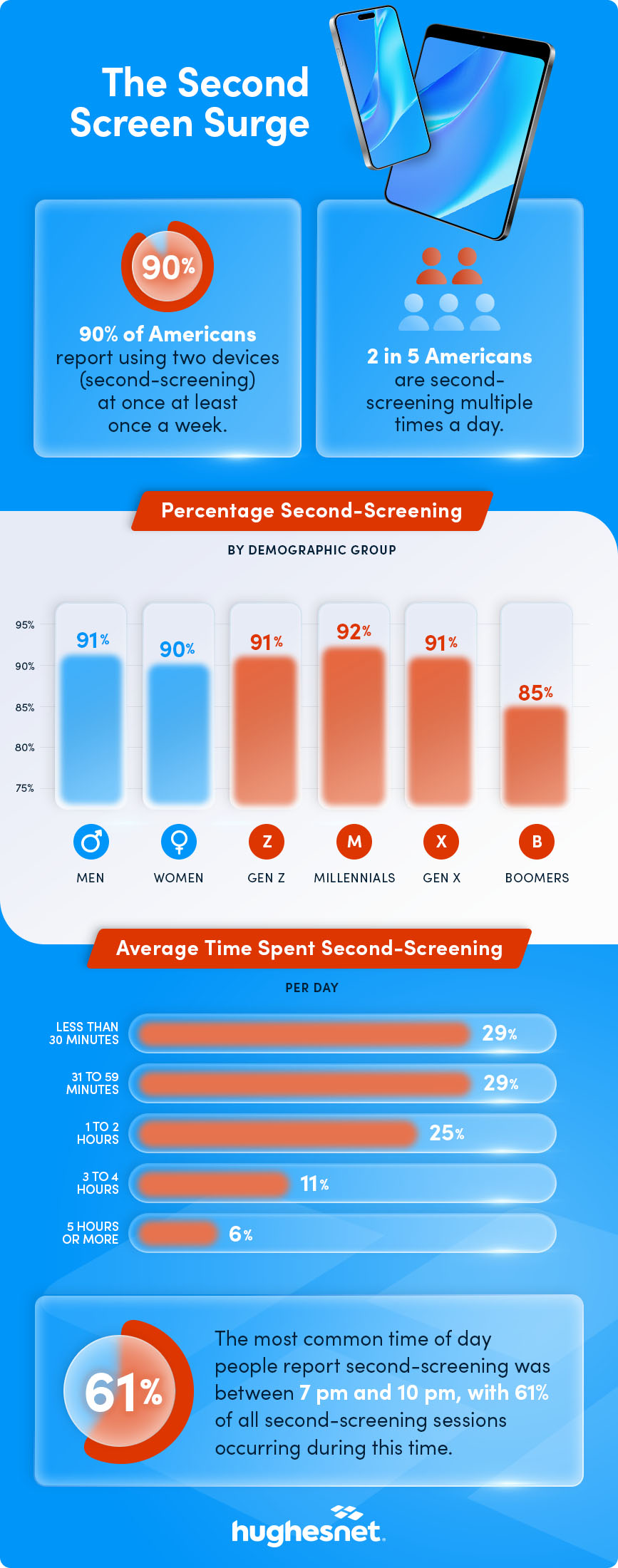

The survey showed that most of us second-screen at least occasionally. 90% of Americans report using two devices at once at least once a week, with two-fifths reporting they use the second screen multiple times a day, and 42% use two devices at once for more than an hour a day.

Breaking things down by gender, men and women are equally likely to second-screen. There were signs that media multitasking has a generational component: boomers were less likely to second-screen than younger generations, though only by 6-7%.

Phones, TVs, and Laptops

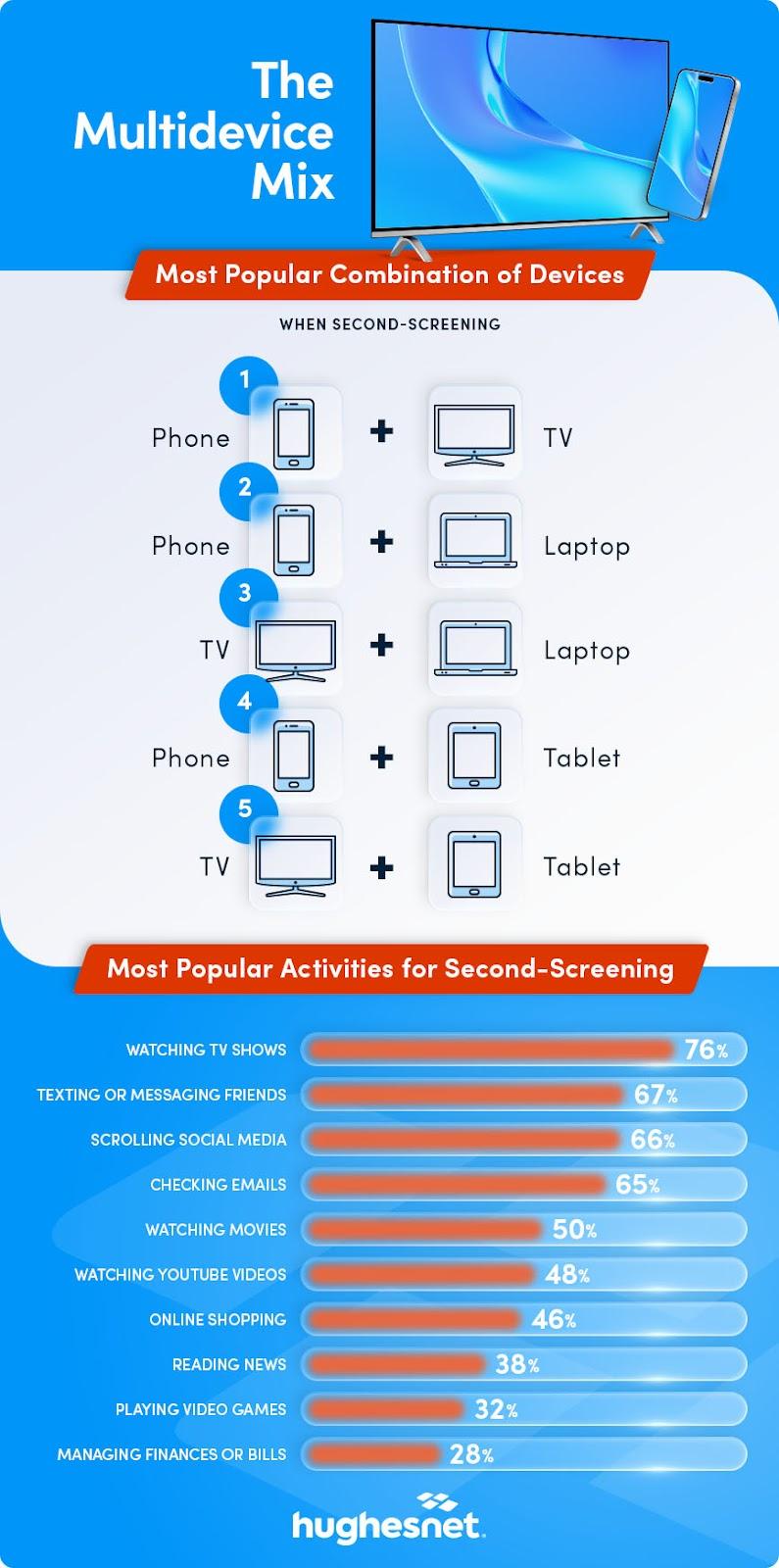

So what are we doing while we’re second-screening? The most common device combo is phones and TVs, which account for 53% of multi-device use, followed by phone and laptop, TV and laptop, phone and tablet, and TV and tablet.

While we’re watching shows and movies, we’re texting friends, scrolling through social media, shopping, and playing games. A surprising 28% report managing their finances and paying the bills. Doing so seems like a risky venture, as mistakes could easily sneak into your budget if most of your attention is on a show!

Second-screening at Work

Except for doing the bills, the worst that’s likely to happen when second-screening at home is you miss an important part of your show (although distracted shopping could lead to absent-minded purchases you might come to regret). Work, however, is a different story.

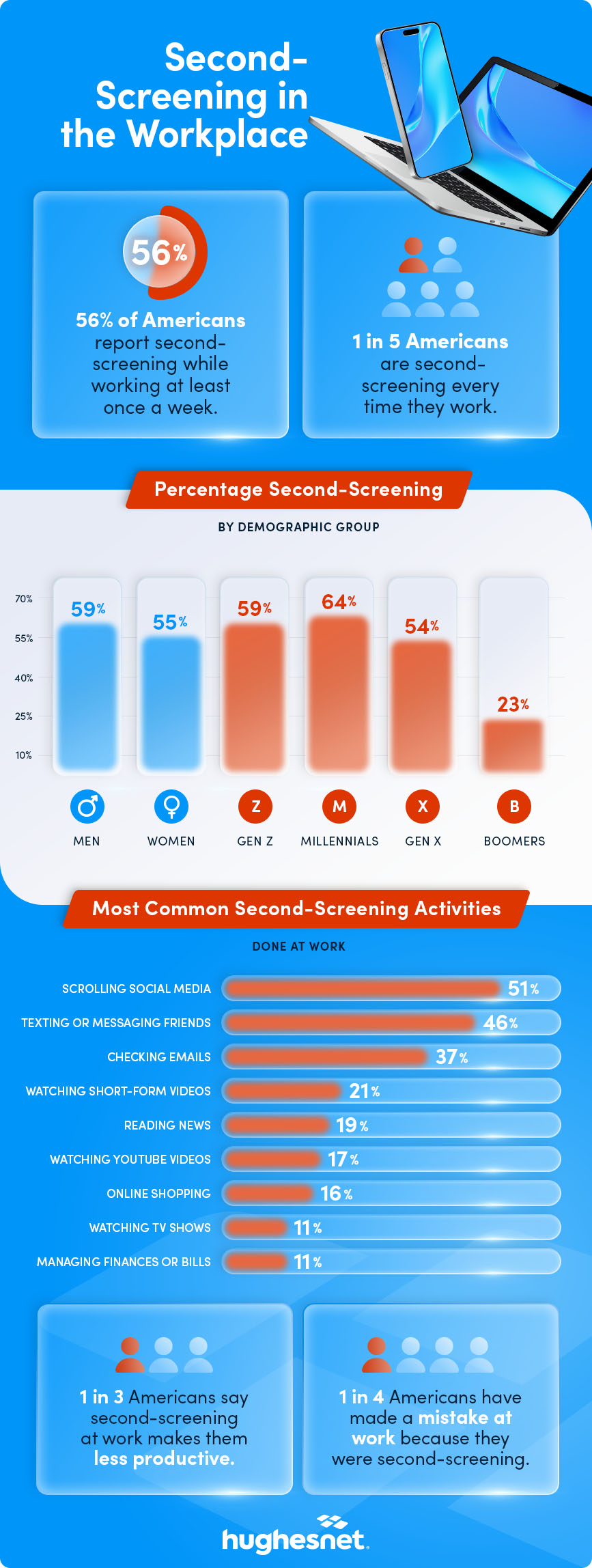

Perhaps unsurprisingly, 56% of Americans report second-screening at work at least once a week, with 20% second-screening every time they work. Millennials are most likely to report second-screening at work, with 64% reporting doing so at least once a week. (Before other generations pile on Millennials, it’s worth pointing out their second-screen at work is only 8% more than average. Multidevice use at work seems to be a multi-generational issue.)

Second-screening at work can have consequences. A third of respondents say second-screening makes them less productive, and 25% report making mistakes at work while using multiple devices.

While this may seem like a serious issue for employers, it’s worth remembering two things. First, 66-75% of respondents didn’t report any problems with workplace second-screening. Secondly, online distractions have been part of work since the adoption of the internet. Is second-screening any different from always having a browser tab open to a personal social media page?

Second-screening and Attention Spans

All this second-screening must be hurting our attention spans, right? Beyond the predictable relationship excessive screen time and a sedentary lifestyle have on fitness and BMI, there’s little scientific consensus on whether, and to what extent, multidevice use affects attention levels.

Survey respondents indicated they felt multidevice use reduces their attention spans, with 30% saying they feel more distracted after second-screening. Over 50% of respondents say their attention levels have dropped due to second-screening, with 10% reporting significantly shortened attention spans.

In all, 66% of Americans are concerned enough that they're trying to reduce how much time they spend second screening, using tactics such as:

- Turning on Do Not Disturb or Focus mode

- Putting their phones in another room

- Turning off app notifications

- Replacing screen time with another habit

- Watching TV with others to remain more engaged

Media Multitasking by State

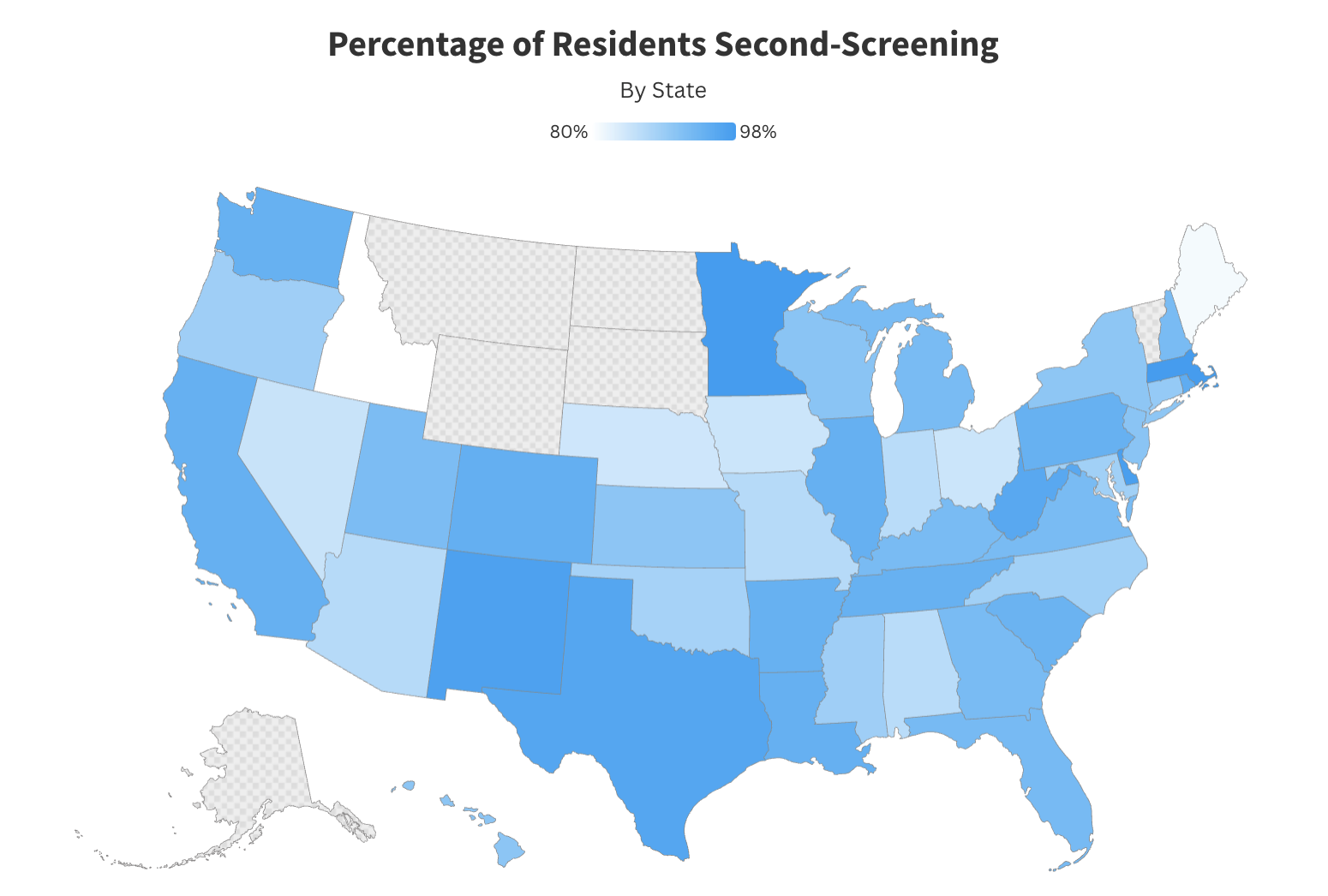

Wondering how your state compares to others when it comes to second-screening? The practice is most common in Minnesota, Massachusetts, and Delaware, and least common in Idaho, Maine, and Nebraska. Before you get too full of state pride (or shame), know there’s not much difference between Massachusetts’ 98% second-screening rate and Idaho’s 80% rate. Turns out we’re second-screening across the nation.

Will the Second-screening Trend Continue?

Like anything else, technology trends wax and wane over time, with only a few becoming a permanent part of our lives. Whether second-screening proves temporary remains to be seen, though the extent to which people use two devices simultaneously suggests it’s not going anywhere soon.

The solution is not to force yourself to use only one screen at a time. Instead, it’s about choosing when and where you want to second-screen and being mindful of the possible consequences. Second-screening at home isn’t going to get you into trouble: using your phone at your work monitor might.

If you enjoy second-screening, you need a home network capable of supporting multiple devices and a reliable internet provider. If you live in a remote or rural area, consider Hughesnet satellite internet so you can keep messaging your friends while you watch your next episode of must-see TV.

Methodology

To determine how second-screening is sweeping across the nation, we surveyed 2,129 Americans about their experiences with technology. Among them, 38% were men and 62% were women. Additionally, 10% were Baby boomers, 31% were Gen X, 44% were Millennials, and 15% were Gen Z. For state-level analysis, each state had at least 45 respondents except for: Alaska, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming, which were therefore excluded from state-level analysis.